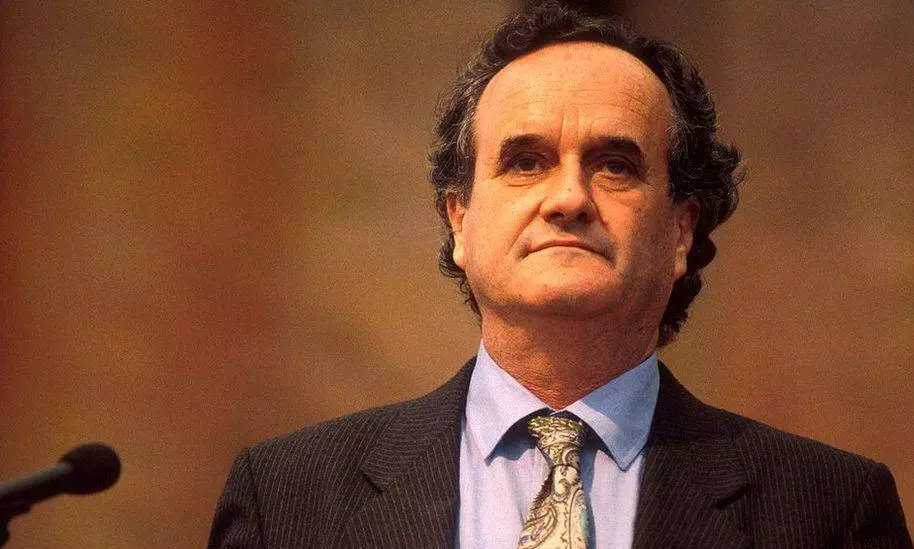

The departure of Mark Tully

text_fieldsOn January 25 Tully died in New Delhi at the age of 90. Mark Tully was best known for being the main BBC correspondent in South Asia from the 1960s to the 1990s. His death marks the passing of an age. He is the last white British journalist of note to have been born in the Raj. When he was the BBC bureau chief in New Delhi in the 1980s, he had to cover Pakistan and Afghanistan as well.

Mark Tully was well-regarded by most quarters in India. Indeed, very rarely for a foreigner he was awarded two of India’s highest decorations. That has led some to suggest he was biased towards the establishment. His admirers will remember him for his accurate reportage, fairmindedness, self-deprecating mannerliness and never-failing good humour. Despite the many frustrations and dangers of journalism in war zones, he was not known to lose his temper or use bad language.

All notable figures in South Asia from the 1960s on knew Mark Tully. From Bollywood film starlets to tech billionaires to Pakistani dictators – they had all met him. He had met every Indian Prime Minister from Nehru onwards. When he began to broadcast in the 1960s, independent Indian broadcasting was relatively new. BBC Radio still had a far bigger listenership proportionately than it does today. Many tuned in their sets for the familiar, ‘bip, bip, bip, beeeeep, this is London’ followed by the jaunty strains of the BBC’s signature tune Lilibulero. Therefore, for a generation of people in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan; Mark Tully was the voice of the news.

In 1935 Tully was born aptly enough in Tollygunge – the chi chi suburb of Kolkata complete with its own Tollygunge Club. His mother had also been born in India. His father was a highly successful businessman. Mark Tully grew up in relative opulence with plenty of servants. The Second World War broke out when he was little. The Bengal Famine killed millions, but the Tully family still lived in the lap of luxury. His parents' only worry wasthat their son would acquire and Indian accent. He was only permitted to socialise with European children. Although he was the second generation born in India it was dinned into him that he was not Indian. Mark later went to a boys’ boarding school in India that was strictly whites only. Nevertheless, he learnt fluent Hindi.

After the Second World War he was sent to a boarding school in the UK: Marlborough College. Originally it was only for the sons of Church of England priests. By the 1940s it was for anyone who could afford the hefty fees. He was considered a rather exotic specimen there and said he had trouble accepting a country he had not seen till he was 11 was ‘home’ as his parents insisted. He later graduated from Cambridge University. He studied to be ordained a priest but dropped out of the seminary as he doubted that he was sufficiently moral. Then he found employment with the BBC in India.

Tully brought his wife with him, and his four children were born in India. Most BBC journalists considered India a hardship post. They wanted to spend a couple of years in India before returning to the UK or some Western country for a plum job. Tully was different – the committed. He said he felt at home in India as he did in the United Kingdom. He observed that despite most Indians being elated about independence even twenty years after independence there was still automatic deference towards him as a white man and especially as a Britisher. He was simply assumed to be high status and intelligent which disturbed him. He was sometimes the only Western journalist to get to the scene and American networks relied on him as they did not trust communist-tinged India. He had a knack of using charm, blandishments, his good reputation and his mastery of Hindi to gain access to places and people that were beyond the reach of other foreign journalists.

Mark Tully reported on most of the crucial South Asian news stories of the second half of the 20th century. He reported on the Second Indo-Pak War, the Third Indo-Pak War, the storming of the Hari Mandir, the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi and the Babri Masjid controversy. His reportage about the Babri Masjid enraged Hindu fanatics who chanted ‘death to Tully.’ It was only the intervention of a brave Brahmin that saved him. Some of his reporting was too candid for the taste of Mrs. Gandhi and he found himself deported in 1975. 18 months later the emergency was over, and he was allowed to return. For some, this signalled the restoration of normalcy.

One of the scariest moments in Tully’s career was meeting Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale in the early 1980s. The Sikh separatist was a ferocious character. At a news conference Tully and the other journalists had to sit on the floor to listen to Bhindranwale’s harangue. Tully is a notorious fidget, and his foot accidentally touched the scabbard of Bhindranwale’s sword. Bhindranwale shot him a terrifying glare and Tully shrank into himself worried that Bhindranwale might prove how sharp his sword was!

Eventually Tully applied for Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI). This was available to white Britishers born in India. India does not allow dual nationality. OCI enabled him to live and work in India without the need for additional visas but precluded political rights.

To some extent Tully ‘went native’ saying that Westerners tended to be conceited in assuming that West is best and India shall and most copy them. He said the ignorance about how ancient India’s civilisation is and how far ahead it was of Europe in bygone centuries is scandalous. He lamented the lack of the understanding in Western lands of Hinduism and Islam. The West is largely post-religious and this he noted is the biggest fissure between the West and a largely religiously based Indian society.