Teen brain structure changes due to early substance use: study

text_fieldsNew research from the United States highlights notable differences in the brain structures of teenagers who engage in substance use, such as alcohol and cannabis, before age 15 compared to those who abstain.

The findings, published in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Network Open, suggest that some of these brain differences may exist even before substance use begins.

The study, conducted by researchers from institutions including Washington University in St. Louis, analyzed MRI scans from 9,804 children aged 9–11 and followed their development over three years. Of these participants, 3,460 reported initiating substance use before age 15.

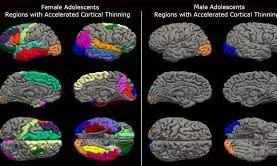

The study revealed five general brain differences and 39 region-specific differences, 22 of which involved the thickness of the brain's cortex. Notably, teenagers who used substances tended to have a larger brain and a thinner prefrontal cortex, a region responsible for higher-level cognitive functions such as planning and decision-making.

Researchers found that these brain structure differences likely existed prior to substance use, suggesting they could contribute to an individual’s risk for early initiation. Alongside genetic and environmental factors, the structural variations in the brain may play a role in determining susceptibility to substance use and addiction.

“This adds to emerging evidence that an individual’s brain structure, combined with their genetics and environmental exposures, influences their risk and resilience for substance use and addiction,” said Nora Volkow, Director of the US National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The study also observed that some brain structure differences appeared unique to the type of substance used. However, more research is needed to understand how these structural distinctions translate into specific behaviors or brain functions.

The researchers emphasized that brain structure alone cannot predict substance use. Instead, it should be considered alongside other risk factors. The findings, while valuable for identifying potential vulnerabilities, should not be used as a diagnostic tool.

The study drew data from the ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, which tracks brain development and mental health in nearly 12,000 youth in the US from age nine into early adulthood.