Delayed trials pressured many Muslims to plead guilty in NIA cases: Report

text_fieldsAs the National Investigation Agency acts under the authority granted by the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and allied laws to keep those it arrests, particularly Muslims, in prolonged pretrial detention while trials and bail hearings are delayed for years, a growing body of evidence suggests that accused persons are being pressured into confessing guilt without being subjected to full trials, even as the agency publicly boasts of a 100 per cent conviction rate, according to The Wire’s investigation.

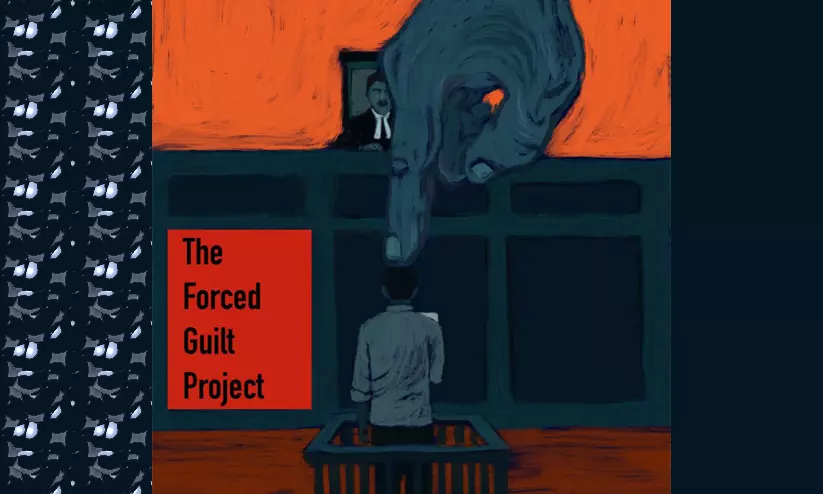

This report is the first article in The Forced Guilt Project, a series by The Wire supported by the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting.

An analysis of NIA case data conducted by The Wire over nearly two years reveals that the Home Ministry’s and the NIA’s claim of a 100 per cent conviction rate is closely linked to the structure of the UAPA, particularly Section 43D(5), which makes bail exceptionally difficult and has resulted in accused persons remaining in custody for years before trials begin.

Following the Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling in the Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali case, courts have increasingly denied bail unless charges are found to be prima facie untrue, a standard that has further narrowed the scope for pretrial release despite later clarifications in the K.A. Najeeb judgment.

As of September 2025, verdicts had been delivered in only a fraction of the cases registered by the NIA since 2009, while many accused have spent close to a decade or more in prison awaiting trial.

In this context, The Wire found that in more than 40 per cent of concluded cases, convictions were secured through guilty pleas rather than full trials, with Muslim men, often from marginalised backgrounds, constituting an overwhelming majority of those who pleaded guilty.

The investigation indicates that prolonged incarceration, repeated bail denials and uncertainty over trial timelines have driven many accused to admit guilt as a means of securing release, sometimes after having already spent more time in custody than the sentence ultimately imposed.

While the NIA maintains that guilty pleas are solely a matter between the accused and the court, court records and interviews suggest a pattern in which confessions function as an exit from an otherwise endless legal process.

The role of trial courts has also come under scrutiny, as judgments accepting guilty pleas frequently follow standardised formats and, in some cases, have resulted in severe sentences later criticised or overturned by higher courts for lack of due process.

On March 21, 2025, Union home minister Amit Shah, addressing the Rajya Sabha, described what he called the government’s success in tackling terrorism by citing the National Investigation Agency’s record of registrations and convictions as evidence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s zero-tolerance policy, echoing the NIA’s December 31, 2024 announcement projecting a 100 per cent conviction rate, up from 94–95 per cent, based on 25 cases.

Established after the 2008 Mumbai attacks during P. During Chidambaram’s tenure as home minister, the NIA has expanded sharply in jurisdiction and resources, even as early concerns raised by Sitaram Yechury over federalism failed to result in constitutional challenges.