Prison for news: a dangerous precedent

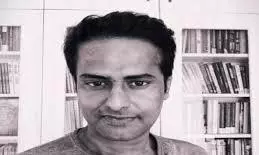

text_fieldsThe sentence handed down by a magistrate’s court in Gujarat to journalist Ravi Nair is yet another indicator of the shrinking space for press freedom in India. Ravi Nair has been sentenced to one year in prison and fined ₹5,000 in a criminal defamation case filed by Adani Enterprises Limited. The company argued that posts and articles he published between October 2020 and July 2021 on “Twitter” (now “X”) and in the Australian publication “Adani Watch” were defamatory. The magistrate, Damini Dixit, held that the journalist was guilty under Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code. The court has granted him one month to file an appeal against the verdict. The argument that the writings were published in good faith in the public interest was not accepted by the court, which is unfortunate. This verdict reinforces the view held by legal experts that criminal defamation laws have been designed to muzzle press freedom in order to protect the interests of powerful corporate entities. There is no dispute that individuals and institutions deserve protection from defamation. However, when civil defamation law itself is sufficient for that purpose, the continued existence of a colonial-era criminal provision like Section 499 lends weight to the criticism that its real intent is to curb even legitimate criticism.

In the words of the global journalists’ organisation Committee to Protect Journalists, the verdict sets a dangerous precedent for press freedom and freedom of expression. The court held Ravi Nair’s posts to be defamatory on three main grounds: that the allegations were repeatedly made, that the posts were accusatory rather than investigative in nature, and that they were widely circulated through social media. The Adani Group pointed out that 17 posts, in particular, had harmed its reputation. The court examined three prosecution witnesses, all of whom were employees of the Adani Group. While the company argued that the posts were written in a manner that cast aspersions on it without proper verification, the defence maintained that the writings were based on previously published reports that had been studied before being shared. The court, after concluding that the company’s reputation had been harmed, observed that the material responsible for the alleged damage had not been published following adequate investigation. In reality, Ravi’s posts included links to articles already available in the public domain and published by several media outlets, including The Guardian, The Times of India and Bloomberg. Some of the posts referred to allegations of corruption involving the Adani Group in Australia, Sri Lanka and India, while others discussed the company’s monopolistic practices. To label such posts as defamatory rather than critical effectively amounts to criminalising investigative journalism itself.

The court also cited the repetitive nature of Ravi’s allegations as a basis for concluding that he did not act in good faith. By that logic, one could argue that the Adani Group’s repeated filing of cases against media organisations and journalists would also not qualify as being in good faith. This raises the question of whether the intent behind such filing of cases is to intimidate and deter even legitimate criticism from being voiced. This is the strategy known as Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs), as pointed out by Reporters Without Borders. RSF has alleged that the Adani Group intensified its legal actions against the media after 2017 and has managed to silence at least 15 journalists, including prominent ones, through such tactics. Although this is the first instance in which a case has resulted in a conviction, temporary injunctions and restraining orders have been imposed on several occasions in the past. While writings and posts produced in the public interest on matters of public importance are generally exempt from punishment under the law, how courts interpret and apply these protections becomes crucial. In short, the sentence awarded to Ravi Nair illustrates how an unnecessary and dangerous law can be used against press freedom, which is the very lifeblood of democracy. Such actions are likely to discourage journalists from exposing corporate corruption and the anti-people consequences of crony capitalism.