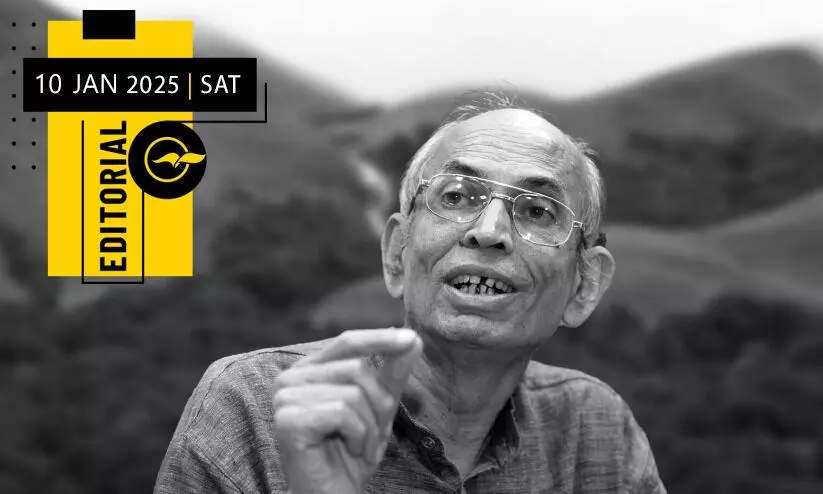

Farewell to a man of nature

text_fieldsThe fundamental philosophy of nature conservation and green politics is that this land and its biodiversity are something our ancestors have handed down to us as a gift for future generations. Dr Madhav Gadgil, who passed away yesterday, was India’s leading environmental scientist who laid the scientific foundation for this vision. It is certain that the void left by the passing of this man of nature, who played a leading role in green politics and policy formulation in our country even before society hailed him as the ‘Guardian of the Western Ghats,’ will be immense. The reason is that the naturalist philosophy Gadgil left behind has become even more relevant in the era of global warming and climate change. At this juncture, in the absence of Gadgil, we have few people left to elevate this vision to new dimensions and to authoritatively question the authorities in this new era of corporatised development. Therefore, recalling and repeatedly speaking about Gadgil, his memories, and his interventions has, in present-day India, become a political act of no small significance.

Also Read:Renowned ecologist Madhav Gadgil passes away at 83

Gadgil is widely remembered over the past decade and a half as the man who devised a scientific plan to protect the Western Ghats. Although the Western Ghats conservation initiative was the most significant chapter in his public life spanning over five decades, he had already distinguished himself long before that as a naturalist, teacher, and expert in policy formulation. Beyond that, his greatest distinction lies in how he contextualised international natural science scholarship and biodiversity knowledge within the country’s unique setting, thereby giving a new sense of direction to environmental studies. Gadgil conducted his research at Harvard University in the United States under the guidance of the renowned Edward Wilson. Wilson was one of the pioneers of sociobiology. Even though he could have continued under Wilson, who made immense contributions to biodiversity studies, Gadgil returned to India, dedicating his research and knowledge to his homeland. It was from this commitment that the Botanical Survey of India and the Zoological Survey of India took shape in their present form. The Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru was his domain. It was while continuing his teaching career there that all of this took place. Not only that, he travelled across the country, working with local environmental organisations to develop conservation initiatives suited to each region. As part of this, he also came to Kerala. He worked here in close association with the Sasthra Sahithya Parishad since the time of the Silent Valley movement. In the 1990s, when the Parishad prepared the Biodiversity Register as part of the People’s Plan Campaign, Gadgil was behind that initiative as well. The most distinctive feature of his biodiversity studies was that they were also a form of people-centric scientific inquiry. It was by considering indigenous knowledge of nature and community-created maps that he prepared his works, including the Western Ghats conservation report. Therefore, it was practical, and the balance between nature, people, and development was evident in the ideas he put forward.

However, it is doubtful whether our authorities sufficiently recognised Gadgil’s pragmatic environmental vision. The way officials dealt with the proposals he submitted for protecting the Western Ghats amounted to crucifying Gadgil himself. By misleadingly portraying the Gadgil recommendations as a scheme to evict residents of the Western Ghats, the political alliance of capitalist development interests threw the report itself into the dustbin. We are now experiencing the consequences of this. Therefore, the question we must raise at this moment is this: Will we, at least now, listen to Gadgil? This question is not new. Over the past decade, Kerala has repeated it at least twice. The first was when Gadgil described the 2018 floods as a man-made natural disaster. In 2024, when landslides occurred in Chooralmala and Mundakkai in Wayanad, Kerala once again cried out, ‘call Gadgil’. It has already been proven that these were natural disasters that occurred when not only were Gadgil’s warnings ignored, but new development slogans were introduced in disregard of the repercussions of climate change. When the landslide disaster struck, he told reporters: “The government and officials are turning a blind eye to the environment and colluding with the interests of industrialists. They cannot evade responsibility for these disasters. Now, they are even constructing a tunnel road through this region. Under the guise of eco-friendly tourism, an ‘industrialist’s’ projects are also taking place there with the Chief Minister’s knowledge. I do not think the government will correct its course. There must be a people’s movement against these environmental encroachments.” Let the question be repeated: Will we, at least now, listen to Gadgil?