Heroism is not to wreck someone’s livelihood

text_fieldsIn situations where it is not possible to go out of the house or workplace due to laziness, rain, or sun, it is the temporary workers of the food delivery firms who bring food to the doorstep immediately as you order through the app on your mobile phone, be it during day or night. It is these gig workers who are relied upon by thousands of customers every day for not only food, but also daily essentials such as medicine, milk, and vegetables. These people who run to the doorstep through heavy rain and scorching sun, overcoming traffic jams and potholes on the roads, in the process also work together to keep the clock of our lives ticking without fail.

The people who turn up before us wearing T-shirts and caps with the names of big delivery companies work on a meagre salary, without any perks or job security. In our country, where unemployment is already acute. The increased job loss after COVID-19 has forced many to choose work in this sector. Many students, including girls, are also entering this field to find money for study and accommodation. From those who want to earn a small income with dignity without seeking the generosity of anyone else, without fearing the harshness of a visible employer, to those who want to find a way to support their families, including parents, senior citizens, ex-servicemen, to former expatriates who have lost their jobs and returned home, every kind of people in pursuit of an income is in this field. The wage cuts and the problems they face from restaurants, customers, and others while working also need to be explained in detail. According to NITI Aayog, there are 7.7 million gig workers in India even though such problems exist in this sector. The estimate is that by 2029-30, this will increase by 200 per cent to 23.5 million.

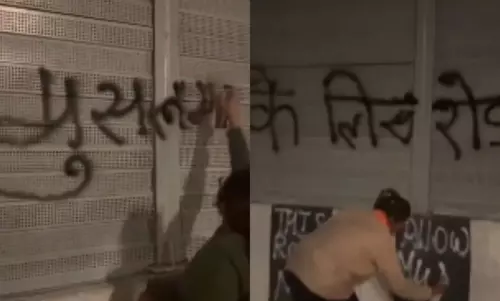

Certainly, the media should report on, and the public should discuss the plight of these people who have become a large workforce in the country. To be held in focus is the pain and suffering they experience, the colourful dreams they see, the rights they are deprived of, the love they displayed while they satiated the city's hunger by crossing the floodwaters without taking a break. Further, thought should also be given to the need for Kerala and other states in India to implement a social security law modelled on the one proposed by the Ashok Gehlot government in Rajasthan. Unfortunately, some media outlets and their associates are eager to create sensational stories about these workers and their working methods, alienating them from society. It is not to be called journalism if it throws these innocent people into a mob trial by releasing a supposedly investigative report on the rumour that drugs are being smuggled under the guise of a food delivery service.

There was a time when in states like Kerala, it was guest workers from other states who were hunted down by such media trials and prejudices because they worked hard to make our lives easier, build houses, and remove waste. Even though they have meshed into an indispensable part of everyday life, there is a sharp edge of suspicion in the Keralites' gaze towards them. Rickshaw pullers and street vendors are all victims of such criminal labelling to some extent. If any gig workers have been involved in any crimes or if the service has been misused for illegal purposes anywhere, those incidents certainly need to be addressed on their merits, but that is different from branding this class as criminals as a whole. Journalists will do well to remember that they will not condone any one who takes up the accusations of some vested interests that journalists are all criminals because one of them was involved in a crime. We urge the public to use this opportunity to speak out for the protection of the rights of gig workers and to the governments of Kerala and other states to take the initiative to enact a legislation that will promote their social security.