Truth on trial in Ladakh: the incarceration of Sonam Wangchuk

text_fieldsI first heard about Sonam Wangchuk when I watched 3 Idiots, the 2009 film that mocked India’s exam-obsessed education system. The main character, Phunsukh Wangdu, played by Aamir Khan, was based on this real-life engineer and innovator from Ladakh. Over time, Wangchuk became more than an educationist — he turned into the moral voice of a neglected region that lost its autonomy and dignity.

I met him briefly in 2022 when he received the Paulos Mar Gregorios Memorial Award in Delhi. The award citation mentioned his solar-powered tents for soldiers serving on the icy Himalayan front and his famous ice stupas — artificial glaciers that store water in winter and release it in summer. He spoke softly and clearly, with the calm confidence of a man who lived by his convictions.

His speech that evening was unforgettable. He said that while wars and murders had reduced over time, deaths caused by climate change were rising rapidly. Every year, about a million people die in floods, cloudbursts, melting glaciers, and storms — all caused by global warming.

Yet, he said, religious and political leaders seemed unconcerned. “When you live simply in the cities,” he urged, “we in the mountains will also be able to live simply.” His message was that the biggest violence today comes from greed and overconsumption, and peace now means protecting the planet.

Yet, this same Wangchuk once welcomed the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, when Home Minister Amit Shah removed Jammu and Kashmir’s special status and divided it into two Union Territories. He and AAP leader Arvind Kejriwal both supported the move. It seemed strange to me. Kejriwal’s politics is all about full statehood for Delhi, while Wangchuk had long defended autonomy for Ladakh. How could they support a law that ended statehood for an entire region?

Soon, the people of Ladakh realised what they had lost. Their Hill Development Council, which once gave them some self-rule, became powerless under a centrally appointed Lieutenant Governor. Ladakh — larger than

Jammu and Kashmir, combined, and 97 per cent tribal, was left without its own legislature, civil service commission, or control over land and jobs.

The ideas Wangchuk now speaks for are not new. They were first voiced by Kushok Bakula Rinpoche, the revered monk, freedom fighter, and diplomat who represented Ladakh in Parliament for decades, often elected unopposed. I had met him in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, when he was India’s ambassador there.

He was so respected that people queued outside the Embassy every morning to meet him. He had fought for autonomy for Ladakh within India, and it was through his efforts that an autonomous Hill Council was finally created.

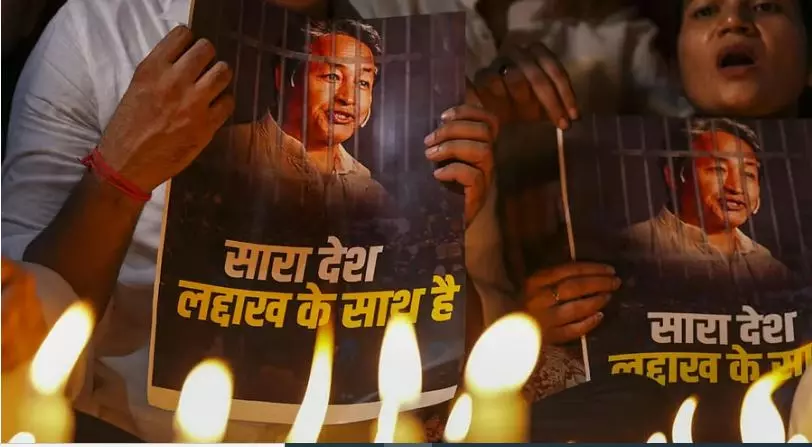

That council virtually vanished when Ladakh became a Union Territory. Wangchuk took up Bakula’s cause. In 2024, he led a peaceful march from Leh to Delhi — a journey of hundreds of kilometres — to demand constitutional safeguards for Ladakh. His main demands were statehood, inclusion under the Sixth Schedule, which gives tribal areas some protection over land and resources, a separate public service commission, and an extra Lok Sabha seat for the region.

But when his group reached Delhi, the government panicked. The police stopped them at the Singhu border, detained them for over 24 hours, and took them secretly to Rajghat at night. The government feared that if the march was allowed, thousands would join in. Ironically, even the British had allowed Gandhi to complete his Dandi March.

A few months later, tragedy struck. On September 24, violence and arson broke out during protests in Leh, and four Ladakhis were killed in police firing. The peaceful movement turned dark that day. Wangchuk did not justify the violence; instead, he demanded a judicial inquiry into what had happened and why. “We want truth, not revenge,” he said. But instead of listening, the authorities arrested him.

Then began a campaign to discredit him. His NGO’s foreign funding licence was cancelled. He was accused of being a “Pakistani agent” because he had once attended a United Nations climate conference in Pakistan — where, in fact, he had praised Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s green policies.

Despite his clean record and public service, his integrity and patriotism were questioned. He was moved to a prison in Rajasthan, where summer temperatures reach 50°C — a cruel punishment for a man from a land of glaciers. His wife was not told the reason for his detention, and because the charges are serious, he may not get bail soon. The Supreme Court could not respond promptly to her habeas corpus appeal.

The message is clear: the government fears not violence but dissent. It brands every protest as anti-national. It did this with farmers who opposed the farm laws, and it is now doing it to the people of Ladakh. The idea seems to be that anyone who questions the government must either surrender or suffer. We have seen this pattern before — as in Gujarat, where Hardik Patel, once jailed for leading a caste agitation, was later absorbed into the ruling party.

But Wangchuk is made of different stuff. His patriotism lies in his work, not his words. He built schools, not slogans; solar tents, not propaganda. His hunger strike and march were for justice, not politics. When he demands statehood for Ladakh, he is not challenging India’s unity — he is strengthening it by asking for fairness. He is, in every sense, a true son of the Himalayas, where courage speaks softly but firmly.

The cruelty shown to him is a stain on our democracy. India has always drawn its moral strength from its margins — from monks in Ladakh, tribals in the Northeast, farmers in Punjab, and fishermen in Kerala. When we silence them, we weaken the nation.

Who’s afraid of Sonam Wangchuk? Not the people of Ladakh, who see him as the heir to Bakula Rinpoche’s vision. It is the powerful who fear him — because his calm words and clean record expose their insecurity. His voice carries the quiet strength of truth, and truth, like water from a melting glacier, will always find its way.