When the court intervenes in the voting machine

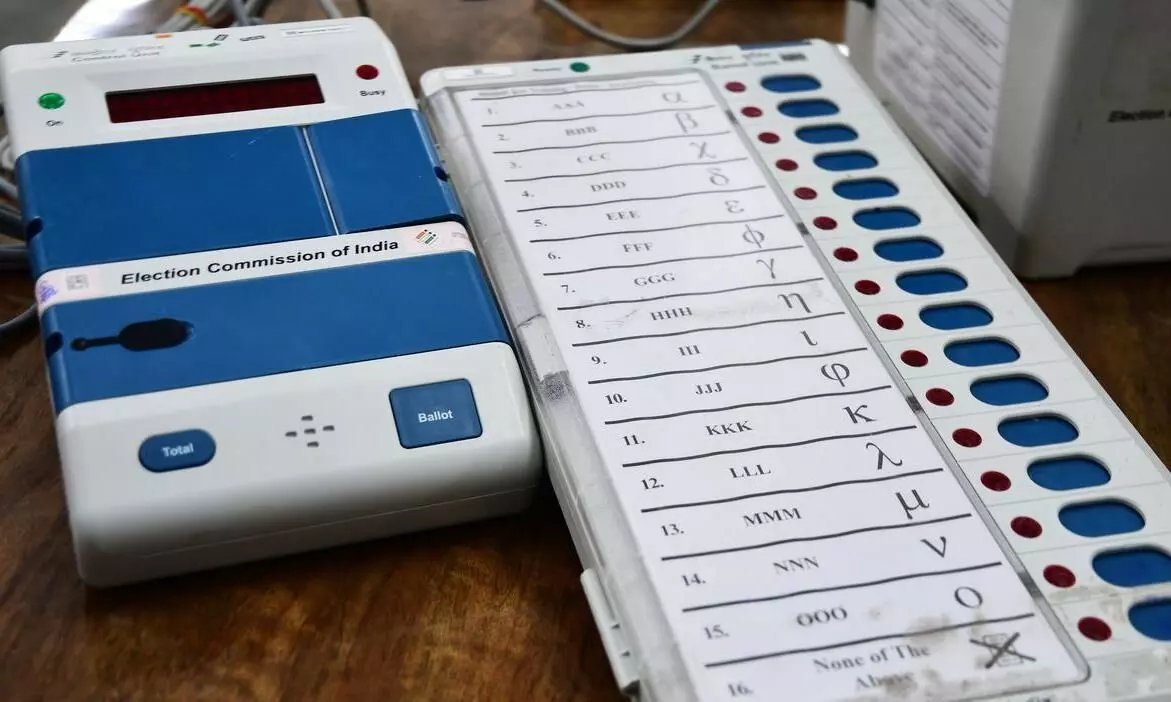

text_fieldsWith only days left before the Lok Sabha elections, the Supreme Court has made a crucial intervention regarding the use of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs). The Court has issued a notice to the Election Commission on a petition seeking the counting of all Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) slips in elections. The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) has filed a petition seeking reforms in the electoral process. The Supreme Court is expected to hear the petition before the first phase of polling on April 19. Although VVPATs are attached to all EVMs used in an election, currently only the slips from five randomly selected machines are counted. The petitioners' main demand is that all slips should be counted, and the total votes should be reconciled. The petition also suggests that there should be an opportunity to keep VVPAT slips separately and that the glass of the VVPAT machine should be made transparent. Recently, concerns and doubts regarding the EVMs have been raised from various quarters. The crux of these doubts is the possibility of tampering with the EVMs to overturn the election results. These allegations, supported by experts in the field with concrete evidence, cannot be dismissed as mere conspiracy theories. Although similar petitions have been filed in various High Courts in the country in the past, they were all dismissed at the initial stage.

It has been 20 years since the country started using EVMs for the entire processes. Since then, we have witnessed five Lok Sabha elections. In the meantime, at least four assembly elections have also been held in all states. In every election, the reliability and transparency of EVMs have been challenged. The issue came to public attention and later led to legal battles with the revelations of Manoranjan Roy, an RTI activist, about irregularities in the production and distribution of voting machines. Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) and Electronics Corporation of India Limited (ECIL) are the two public sector undertakings that manufacture EVMs. In 2017, Manoranjan filed a Right to Information (RTI) application with these companies, asking how many voting machines they had manufactured and supplied to the Election Commission over a period of 25 years, starting in 1990. The responses of the companies were 19.6 lakhs and 19.4 lakhs respectively. However, when the Election Commission was approached with the same question, the response differed. BHEL offered 10.5 lakh machines, while the commission's response indicated ECIL's contribution was 10.1 lakh EVMs. There is a significant difference in the answers, which raises concerns. In other words, it is alleged that about 19 lakh machines manufactured by the companies have not reached the Election Commission. Even these 'missing' EVM machines would be enough to rig the Lok Sabha elections. This realization prompted Manoranjan to raise the issue in the Bombay High Court. The case has been ongoing since 2018, but the court has not yet made a definitive ruling on the matter. The matter has dragged for so long because of the Election Commission's indifferent approach. It was only after the voting machine issue went to court that the Commission decided to attach VVPATs to the machine and try to assuage the criticism. The Commission's position is that counting a nominal number of VVPATs will ensure transparency, while they argue that counting all VVPATs would be a waste of time. The Commission is likely to reiterate these arguments in the Supreme Court as well. However, it remains to be seen how far the Supreme Court will accept them, given the recent spate of revelations about the voting machine.

It is true that even if all VVPAT slips are counted, doubts related to the voting machine will not completely disappear. There is still uncertainty about whether VVPAT can truly ensure that the vote cast is recorded accurately for the intended candidate. While VVPAT prints and shows the voters who they have voted for, questions remain about whether the same data is indeed recorded in the control unit of the voting machine. Ultimately, votes are counted based on the information stored in the control unit. When a voter presses the button next to a symbol on the Voter Ballot Unit, the VVPAT only prints it. However, there's no confirmation that it has been accurately transmitted to the Control Unit. Therefore, the primary advantage of counting the entire VVPAT is to ensure the accuracy of the total votes polled. Nevertheless, the petition filed in the Supreme Court remains important. It will definitely raise crucial questions there regarding the transparency of the voting machine.